1.3 Genes and the central dogma#

Scattered throughout our genome are regions called genes which encode proteins. The human genome encodes around 20,000 protein-coding genes (although the exact number is up for debate). Genes vary dramatically in size, and can span anywhere from hundreds to millions of bp.

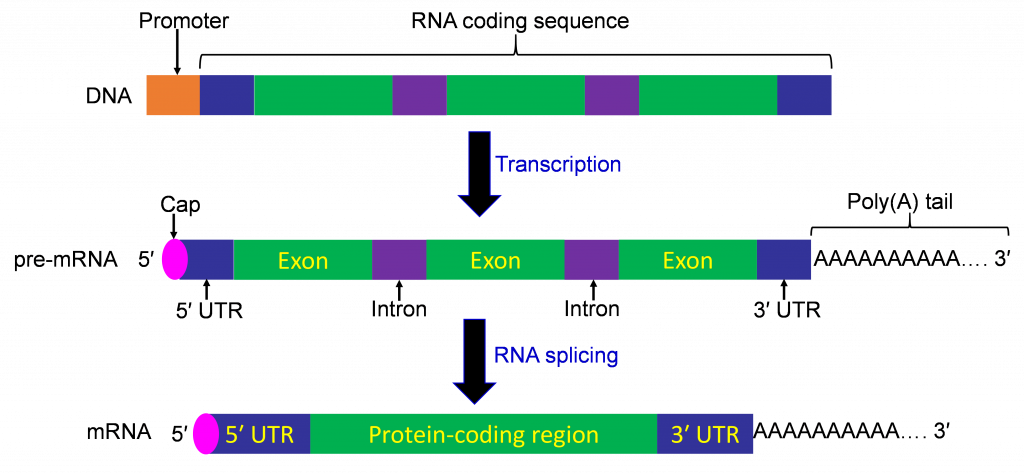

Genes consist of several main components:

Exons usually code for the actual sequence of the protein

Introns are (often quite long) sequences between exons that do not actually code for sequence of the final protein

There are also often untranslated regions (UTRs) at the 5’ and 3’ ends of proteins which encode important regulatory sequences. Technically, UTRs are considered exons but they do not actually get translated into proteins.

Source: Libretexts Biology

Source: Libretexts Biology

The central dogma describes the process by which DNA is converted into proteins. It can be summarized as “DNA->RNA->Protein”. Briefly:

DNA encodes information required to make a protein in the form of a gene.

Genes get transcribed into an intermediate molecule, RNA (ribonucleic acid). RNA is similar in structure to DNA, except it is single stranded, and has bases A, C, G, and U rather than A, C, G, and T. After transcription, the RNA is further processed through splicing, which removes the intron sequences between the exons. While spliced out, the introns often contain important sequences that help regulate splicing and other processes. This spliced form of RNA is referred to as messenger RNA, or mRNA.

Finally, the mRNA is translated into protein. Translation happens according to a precise genetic code. Every 3bp of the RNA (non-overlapping) forms a codon which codes for a specific amino acid, which proteins are composed of. For example “UUU” encodes the amino acid phenylalanine. Proteins always start with a start codon (AUG, which codes for methionine) and ends with one of three possible stop codons (UAA, UAG, or UGA). The table below shows the amino acid coded for by each possible codon.

Source: Office of NIH History

Source: Office of NIH History

If an individual has a mutation in part of the genome that codes for the protein, that mutation can in some cases affect the final protein sequence, which can affect the protein’s function and ultimately lead to changes in a trait or disease risk. Mutations in protein-coding regions often result in one of the following changes:

synonymous mutations change a codon but do not have an effect on the final protein sequence. For example, a change of “UUU->UUC” has no effect, since both codons code for phenylalanine.

missense mutations change the amino acid a codon codes for. For example, a change of “UUU->CUU” changes a phenylalanine to a leucine.

nonsense mutations change a codon for an amino acid to a stop codon. For example, a change of “UUA”->”UAA” changes a leucine to a stop codon. If a nonsense mutation happens near the beginning of a protein, it can result in a severely truncated and non-functional protein product.

frameshift mutations result from insertions or deletions of a number of bp that is not a multiple of 3. This shifts the reading frame of the entire subsequent sequence. If a frameshift mutation occurs near the beginning of the protein, it can have dramatic results on the sequence and function of the protein.

Recall humans have two copies of the genome, and therefore we have two copies of most genes. In some cases, mutations only have an impact if they are present on both copies of the gene (recessive effect). In other cases, having a mutation in one copy of the gene is enough to have an effect (dominant effect). We will discuss this more, including specific examples of disease-causing mutations, in future modules.